Memories of Coloring

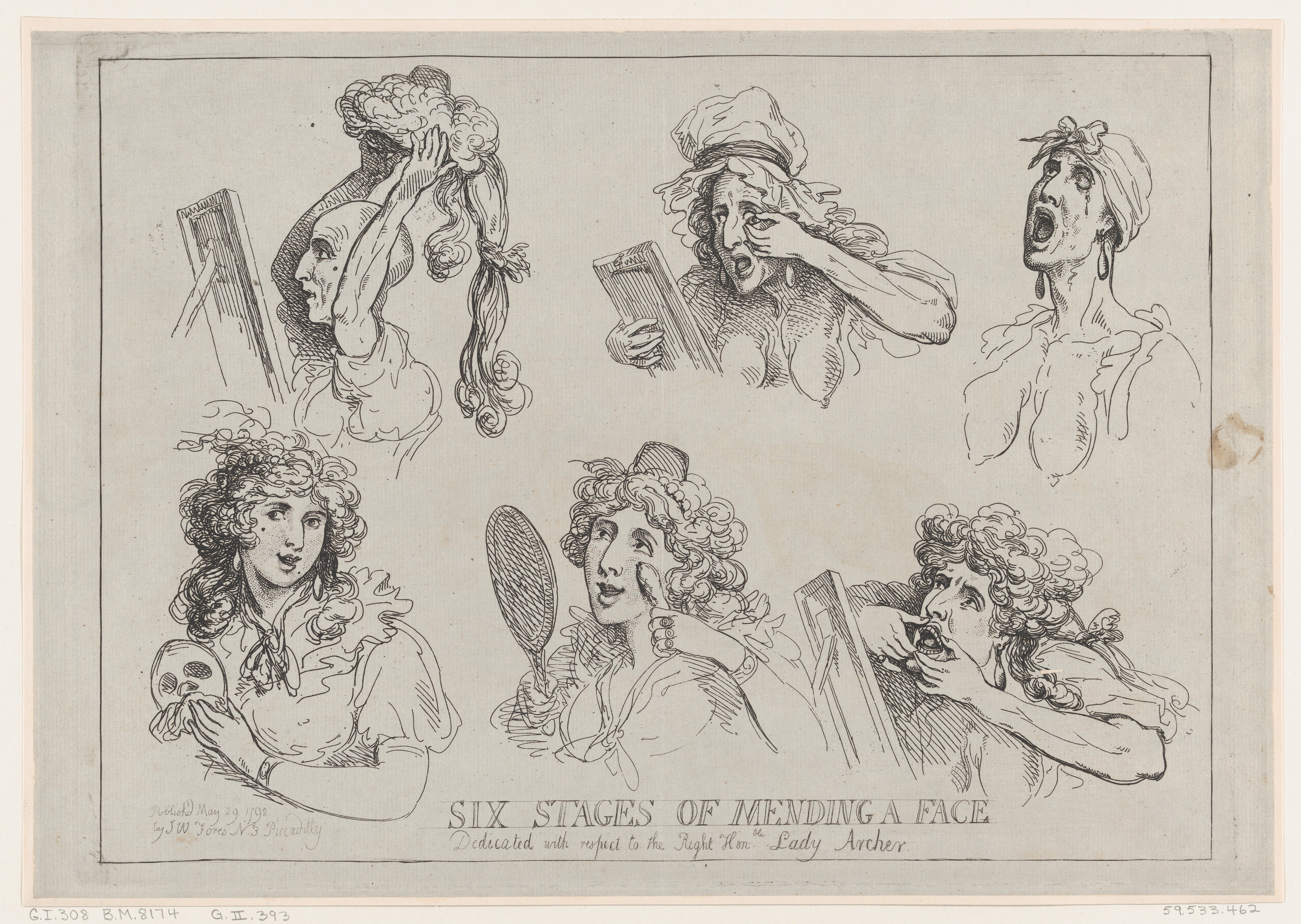

Six Stages of Mending a Face, 1792, Thomas Rowlandson

Some combinations of color are particularly unforgettable: they can bring back a place, a scent, a gesture. The night sky in Shanghai on the eve of a typhoon, deep purple tinged with the greenish yellow of a firefly’s tail; the green malachite in a souvenir shop, polished and chiseled, tied with a Chinese knot of bright orange and scallion green; the sea, still blue in the distance, that shifts to white as it reaches the gravelly beach in foamy breakers, changing color every few seconds—aren’t these practically miracles?

There are miracles in the studio, too. I’ve never forgotten the first time I applied a white gofun glaze to a silk scroll. Days earlier I’d dyed the silk repeatedly in oil-smoke ink and tea, colors which didn’t simply establish a base but penetrated the sparse fibers of alum from either side, seeping into the silk. Changing the color of the thread also changes its essence, and the gofun glaze added after this treatment is entirely different from the original white of the fabric, or any other white. It’s like a ghost that’s a brushstroke away covering the sinews of the silk: if you move the brush, the white moves forward; if you don’t, it pools and settles.

Only in the last few years have I come to understand that a painting doesn’t start from zero, despite what Philip Guston says, quoting something he heard from John Cage: “When you start working, everybody is in your studio—the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas—all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving, one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you’re lucky, even you leave.” Of course, I’ve experienced, to varying degrees, moments of the kind Guston describes, when I float in the studio like the math professor with amnesia in that Yoko Ogawa novel. Stubbornly, though, I think that maybe I don’t have to leave, maybe I can stay. And I can also celebrate the foolish, selfish desire to continually describe, accumulate, incubate, excavate, rebuild, and witness everything anew. It took me several years to realize that if I did leave my paintings, I wouldn’t have learned that colors don’t start from zero.

Before I was born, my parents moved from Taipei and Taichung to a less developed city on the east coast, where the lower cost of living and land prices allowed my father to make his dream of running a farm a reality. Our life on the outskirts of town consisted of raising cows, plowing the fields, and chasing rabbits, until eventually we all moved back to the city so my sister and I could start school. In the local schooling system, thousands of people sit in the same room learning to feel the same things and yearn for the same future. While there I lived the same life as everyone else. One day in third-grade art class, our teacher wheeled in an cumbersome old-fashioned television set and played for us the news of the two passenger jets crashing into the Twin Towers in New York. It was as if she feared we would otherwise miss these powerful images. The reporter stood on a corner in a city I hadn’t yet visited, under a sky filled with dust and on streets covered in paper. For a long time that was my image of the apocalypse: sheets of paper, blank or filled with complicated and now meaningless numbers, falling to the ground, floating this way and that like a loose pendulum, witnessing unfathomable horror as it fell to the ground. Years later, I would read Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, whose narrator describes watching news clips of these events: “Each time I see the woman leap off the Seventy-eighth floor of the North Tower—one high-heeled shoe slipping off and hovering up over her . . . her blouse untucked, hair flailing, limbs stiff as she plummets down, one arm raised, like a dive into a summer lake—I am overcome by awe, not because she looks like Reva . . . but because she is beautiful. There she is, a human being, diving into the unknown, and she is wide awake.”

I went to a high school for girls with twelve in a class, and between school and play, the landscape that lay before me had a purpose. I’d never been given a blank space for my creative autonomy to grow. All the blank surfaces came either from a bucket of white paint poured out in a thick coat over the colors before me, or the desktops where I had to fight to clear a space among the cheap, sturdy knickknacks or costly, fragile items. This is a place that’s been set aside, they said, like a piece of silk painstakingly prepared over days or even weeks, or a primed gesso base, or a hand-polished woodblock. Whoever it’s given to—regardless of whether they leave or they stay—must keep this in mind.

When I was seventeen, I came to Taipei for my college entrance exam, and for the interview I put on makeup. On my face, my mother’s liquid foundation looked extremely pale. She’s always been much whiter than I am: my Japanese-speaking grandfather has pink skin and silver hair, and according to my mother has Dutch blood. But that’s not a story shown on my face, and the foundation I applied looked dry and ridiculous. After the interview I went to the restroom to wash it off, and the water from the tap beaded up on my water-resistant skin like old soap moistened in the bath. I thought to myself, never again will I dress up as someone else for such an important occasion. Back then I still thought that without makeup I’d be myself.

After I came to Taipei, I tried to reach a compromise with makeup in which each side would yield: I’d use the smallest number of products to achieve the greatest effect—darkening my eyebrows with mascara and spreading lipstick on my cheeks. At the same time, whether or not I wore makeup at all made little difference, because in the moral framework of capitalism, a female face worth looking at is a feminist project: she should be organic and unassuming, disciplined and dedicated to her work; the time and labor once spent on her family can be liberated and put toward the project of “self-care.” I also wonder, of course, why I should use makeup in the first place, if it makes so little difference. Yet stepping outside the moral framework always brings extra trouble.

One time when I was home for summer vacation, I offered to do my mother’s makeup. She’d spent a lot of time outdoors and gotten a tan, though notlike the olive brown tans I get. Throughout my childhood, people said I looked nothing like her, and I always agreed, but I seem to have never closely studied her face until that moment. In makeup my mother was beautiful, even if she didn’t quite look like herself.

Strangely, ever since then, whenever I apply a gofun glaze to a silk scroll, with one brush dipped in water and another in pigment, I think of my mother. Or perhaps it’s not so strange after all: for thousands of years, from ancient Rome or the Tang Dynasty to 16th-century France, people have eagerly applied color not only to ceramics, textiles, and paintings, but also to women’s skin: white lead soaked in vinegar for the face, neck and shoulders; elderberry pulp and mouse tail for the eyebrows; cinnabar for the lips, made from mercury sulfide; carmine for the cheeks, made with cooked shellac derived from insects. Colors come and go from the dressing table, and each one ends up smeared onto the painter’s palette. Perhaps before I learned to paint, it was makeup that taught me how to listen while I read, to paint while I look. Since every daughter’s mother is also a mother’s daughter, mothers and daughters can easily spot the differences between themselves—not just because they share a physical resemblance, but because their lives too, if they wish, can be so similar.

Applying color is a form of makeup, a careful examination of the face before you. Today I can see my mother’s face in my own. If I look cruel, it’s only because I have choices she did not; if I’m conflicted, it’s only because I refuse to follow the path she took: even as my hands cling to her experience I hold myself to the expectation that I’ll take a different course. When I look at a canvas, a scroll, a surface primed with mud, I don’t feel at all like an artist—I feel like a daughter. Before I lift my brush, I want to spend as long as possible humbly, critically learning to truly care about this face, a face that has blushed and gone pale, has seen unimaginable horror from high above. This face is the bit of space that they’ve made for me to start coloring.